Singing was always a big part of Antoni Gaudí’s project for the Sagrada Família. In this post, with Junta Constructora architects Umberto Viotto and Narcís Laguarda, we will discover how Gaudí imagined the choirs (the spaces for the choirs) and their acoustics, or how he wanted the singers placed.

Singing that fills the Temple

Gaudí wanted the singers voices to envelop the inside of the Temple to highlight the presence of God. This is why he put the choirs around the space, near the parishioners, 15 to 20 metres off the ground. Putting them at this height takes better advantage of the space and allows the singers to see the altar and the conductor leading them from anywhere in the nave. Plus, as Umberto Viotto notes, the hyperboloid vaults act as a sounding board, with the ceiling reflecting the singers voices and projecting the sound towards the parishioners, like light, so the liturgy can reach everyone. Before the Sagrada Família, Gaudí tested this acoustical effect with the pulpit he designed while restoring the Cathedral of Mallorca, which included a stone sounding board at the top to amplify the speaker’s message.

Replica of the sounding board Antoni Gaudí designed for the Cathedral of Mallorca (left). Vaults above the choirs that reflect the sound and project it towards the nave (right)

«The word, which is the time and vehicle of prayer, must be part of the Temple, where the spaces for the women’s, men’s and children’s choirs will be of great importance. The word will dominate the music»

Cèsar Martinell. Gaudí i la Sagrada Família explicada per ell mateix, page 77

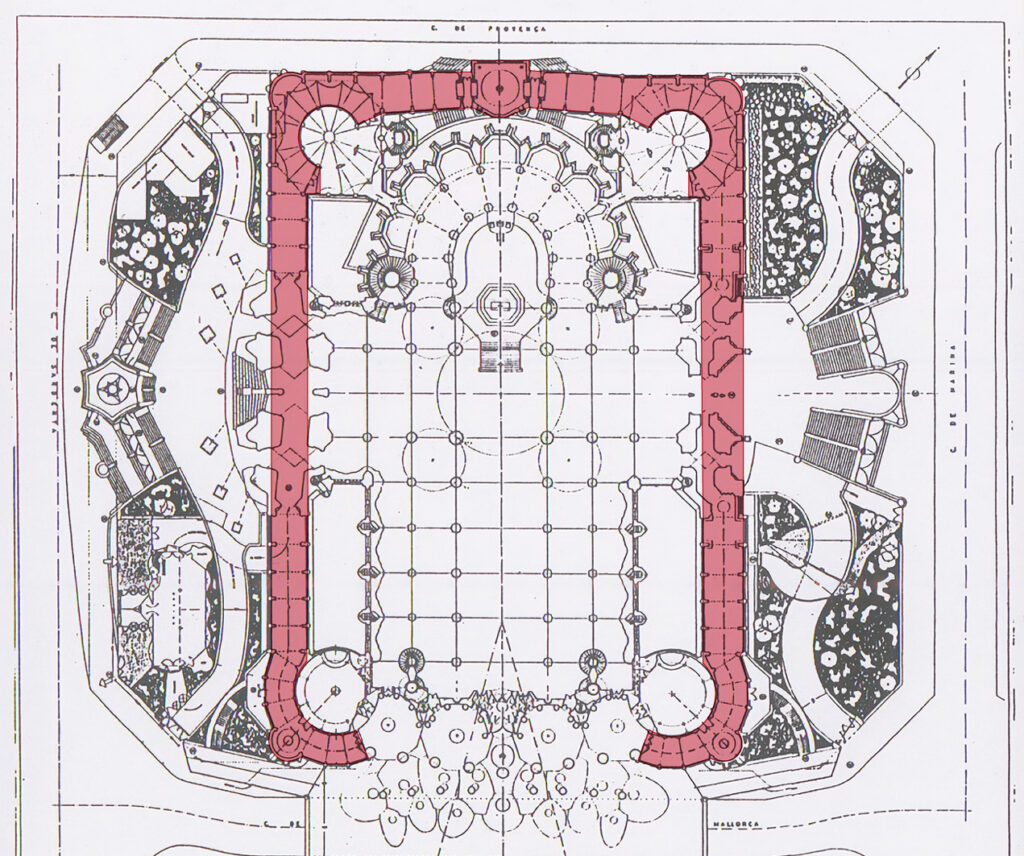

In terms of acoustics, the cloister is also very important. Traditionally, this space was placed to one side of the church or monastery, but Gaudí wanted it to surround the Basilica because he saw it as a place to help keep out the city noise and to pray before going further inside.

Perimeter of the cloister of the Sagrada Família

Regarding placement, as explained in the Àlbums de Temple, Gaudí put the women’s choir along the façades of the side naves and the Glory façade, in a horseshoe shape. Above that, 30 metres up, he designed another space for singers and, above the ambulatory that surrounds the presbytery, in the apse, one for the children’s choir. To round out the choirs, he also described a space in the central lantern, 45 metres up, for the Temple’s musical chapel, among four organs. Finally, over the main door, Gaudí planned a podium or balcony, known as the Jube, for the singing of blessings.

In all, he set aside space for over a thousand voices, which would merge with the faithful singing below during services. “The people have to take part in the Church’s songs", Gaudí told Joan Bergós, the architect’s assistant and friend, who shared it in his book Gaudí. The man and his work.

Also based on conversations with Gaudí, collaborating architect and disciple Isidre Puig Boada wrote that the interior should feature the final hymn of the prayers traditionally sung throughout the day (Matins, Lauds, Vespers and Compline), arranged around the Temple along the sun’s path over the course of the day. In addition to this Liturgy of the Hours Gaudí had already mentioned, there is also the liturgical year, with Advent, Christmas and Lent along the Nativity side and Easter and Pentecost on the Passion side, explains Narcís Laguarda.

The notes for these Gregorian chants appear on the railings of the choirs on tetragram. Plus, each of the 12 sections of choir risers is labelled with the name of the chant, making them easier to identify. Right now, however, only one is in place as an example: “Veni creator Spiritus”.

Musical chapel: group of musicians serving an institution, such as a cathedral or court. It also refers to the way the music is performed, only singers without accompaniment, known as a cappella (“chapel” in Italian), and originally related to the practice of singing without instruments in churches.

Tetragram: four parallel horizontal lines historically used to notate Gregorian chants.

1 comment

jallorens

Muy interesante el artículo