Although today the Basilica of the Sagrada Família is intrinsically linked to Antoni Gaudí, he wasn’t named head architect until 1883, one year after the cornerstone was laid and after architect Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano had stepped down. These circumstances have decisively conditioned the Basilica as it is today.

DEVELOPER OF THE TEMPLE

The construction of the Basilica of the Sagrada Família was begun at the initiative of Barcelona-born book merchant and extremely devout Catholic Josep Maria Bocabella i Verdaguer, who founded the Associació Espiritual de Devots de Sant Josep (Spiritual Association of the Devotees of Saint Joseph) in 1866 in order to foster the values of the Christian family. Four years later, he went to Rome to give Pope Pius IX a silver image of the Holy Family and, on his way back, he discovered the Sanctuary of the Holy House in Loreto. This building enshrines the home where, tradition says, the Holy Family lived and was supposedly moved from Nazareth to this Italian town in the 13th century. Bocabella was extremely impressed by the symbolic and artistic beauty of this Sanctuary, which inspired him to build a replica in Barcelona. And this was the seed of the Basilica of the Sagrada Família.

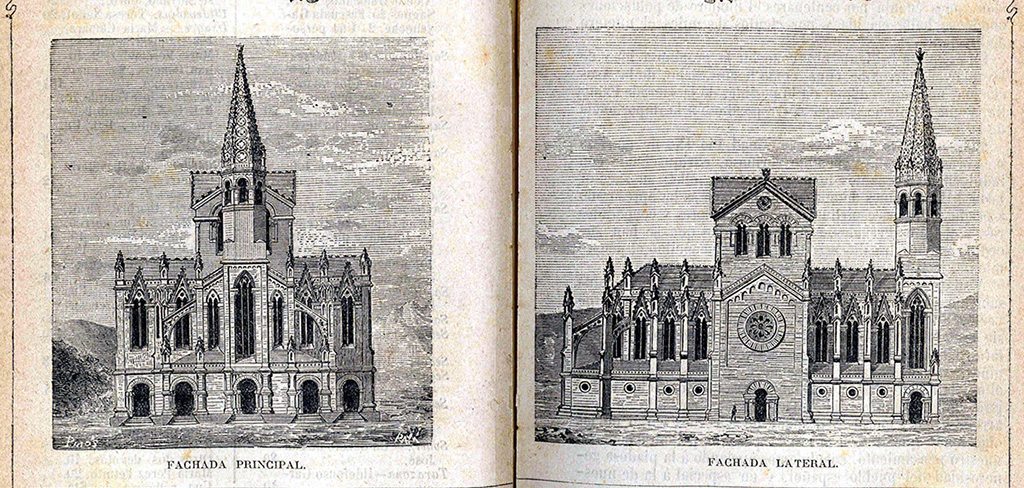

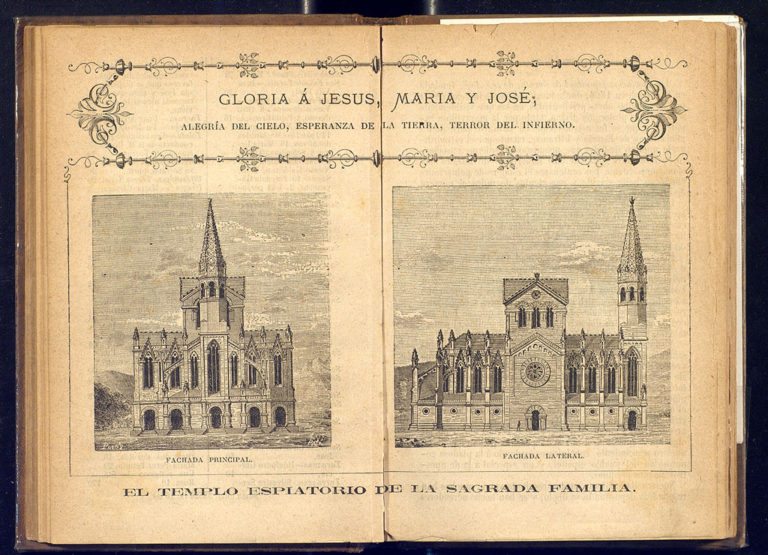

THE ORIGINAL PROJECT: DEL VILLAR’S NEO-GOTHIC TEMPLE

Bocabella entrusted the project to the diocesan architect Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano, who offered to waive his fees. It was an extremely dynamic era in Barcelona, socially, economically and culturally. And it was also a difficult moment in history for Christianity in Europe. This is the context in which Bocabella, intending to rekindle the people’s spirituality, decided that the temple he wanted to build on a piece of land in the Eixample district, which would be paid for with the donations of devotees of the Associació de Devots a Sant Josep, had to be an awe-inspiring building that would convey a feeling of peace to all residents.

Although he dreamt of building an exact replica of the sanctuary in Loreto, del Villar convinced him to discard this idea and build a neo-Gothic temple, as was the trend at the time, while respecting Bocabella’s intention of creating a monumental building.

Del Villar’s project was inspired by the great medieval cathedrals and planned for a church with three naves in a Latin-cross floor plan, a sizeable crypt, an apse with seven chapels and a pointed bell tower located over the portico and rising 85 metres above street level. This verticality, along with the outer buttresses and large cloisonné windows, gave the building a clearly Gothic look.

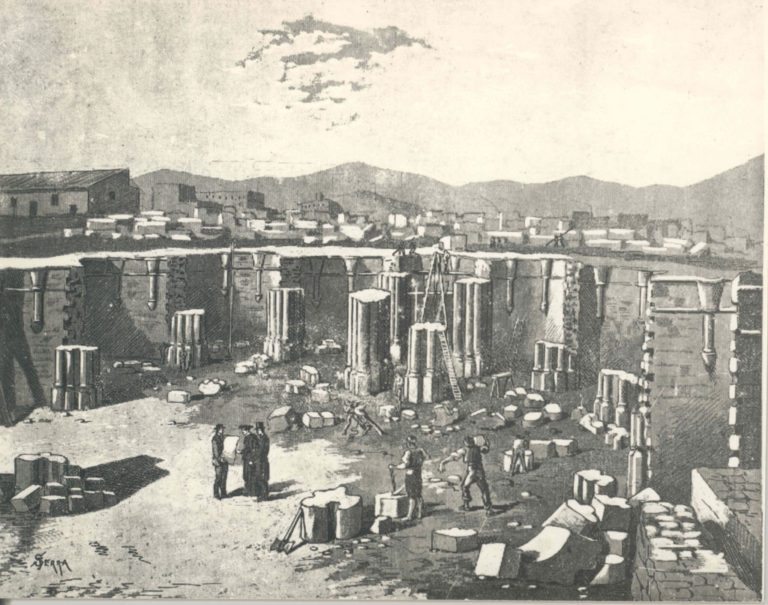

The cornerstone was laid on 19 March 1882, the feast of Saint Joseph, and construction began, as was the custom, on the foundations for the crypt.

DEL VILLAR STEPS DOWN…

One year later, in 1883, the first discrepancies arose between del Villar, on the one hand, and Bocabella and his top advisor, architect Joan Martorell, on the other. Del Villar wanted to use solid stone pillars in the crypt, making each section between horizontal joints a single piece, while the developer and Martorell believed this was way too expensive. Their differences of opinion would drive del Villar to step down for the first time in his career as an architect.

Their differences of opinion would drive del Villar to step down for the first time in his career as an architect.

… AND GAUDÍ COMES ON THE SCENE

After del Villar stepped down, Bocabella offered his position to Martorell. He declined out of professional courtesy and because of his advanced age, but proposed his most outstanding disciple: Antoni Gaudí. He was just 31 years old and had also worked for del Villar.

Gaudí was named architect of the Temple on 3 November 1883 and found a fully drafted project and work already under way: the foundation of the crypt had already been laid and the columns were half built.

Despite being a young architect with only five years of experience, Gaudí tackled this new challenge confidently and enthusiastically, which would end up marking the rest of his career. Right from the beginning, he regretted the orientation of the Temple , as it could not be built diagonally on the land with canonical orientation, facing Jerusalem: the head of the cross (the apse) facing the rising sun and the main entrance (the foot of the cross) towards the setting sun. As the works on the crypt had already begun, however, there was no other option than to respect the orientation del Villar had already established.

THE NEW CRYPT

Nevertheless, Gaudí instated other changes. In the crypt, he made the vaults higher and added flowery, plant motifs on the capitals. He had the windows enlarged and a trench dug along the perimeter in order to improve lighting and ventilation and prevent problems due to dampness. All together, these are clear signs of the new mentality of architectural hygienism and concern for the comfort of the spaces. However the most significant change was eliminating the central staircase and entrance to the crypt. Del Villar had designed a medieval staircase, prioritising pilgrims visiting the relics in the crypt over the rites held on the main floor. Eliminating this central opening from the previous project, which did nothing more than separate the altar from the people, is also a sign of the influence of the liturgical renewal that began to take root in the country, in the same spirit as the Second Vatican Council some 70 years later. The new entrance to the crypt was via two circular staircases, one on either side, which also continued upwards to the highest points of the Temple.

In addition to the crypt, Gaudí had to find solutions for the project he had inherited: the location of the Basilica, chosen by del Villar, for example, puts la the façade of the Temple right on the pavement of the street, which doesn’t allow for a reception space in front of the main doors. Gaudí resolved this by finding space on the other side of the street and designing a bridge and staircase to cross over.

GAUDÍ’S SAGRADA FAMÍLIA

Over the course of just a few weeks, Gaudí completely changed del Villar’s project, not only in terms of its formal and structural appearance, but also in its magnitude and transcendence. He designed the Sagrada Família to be a huge Bible in stone, telling all the history and mysteries of the Christian faith. And he proposed constructing a huge building on a Latin-cross floor plan with five naves, a transept, apse with ambulatory, cloister surrounding the building for large processions, twelve bell towers, six lanterns and three façades. He designed the project according to geometric principles and proportions. Moreover, he hoped to make the Temple of the Sagrada Família a link between heaven and earth and designed the tower of Jesus Christ as the element crowning the Basilica, standing 172.5 metres above ground level.

We will never know for sure what the Temple of the Sagrada Família would have looked like if del Villar had finished the project; and even less what it would be like if Gaudí had been in charge of the project from the beginning. However we do know that, while del Villar wanted to build an awe-inspiring Temple, Gaudí took that to its extreme, uniting faith and artistic genius to transform the Basilica of the Sagrada Família into a universal masterpiece.