The columns inside the Sagrada Família, one of Antoni Gaudí’s most noteworthy contributions to the world of architecture, are unique in shape (double twist) and tree-like structure, which allows them to absorb and distribute the Temple loads.

A new column in the history of architecture

As with other elements of the Basilica the double twist column is born out of Gaudí’s characteristic desire to update architecture and his search for perfection. Using his empirical method, based on testing and correction, the architect strived to create a different sort of column that would update the classical styles of Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns. To do so, he gave the columns a helicoidal upward movement, taking inspiration from the eucalyptus tree he watched grow outside his studio next to the Temple, as Cèsar Martinell explains in his book Gaudí i la Sagrada Família comentada per ell mateix . These ascending helices (typical of Baroque Solomonic columns) draw the viewer’s eye upwards, reinforcing the feeling of verticality and connecting the earth to Heaven.

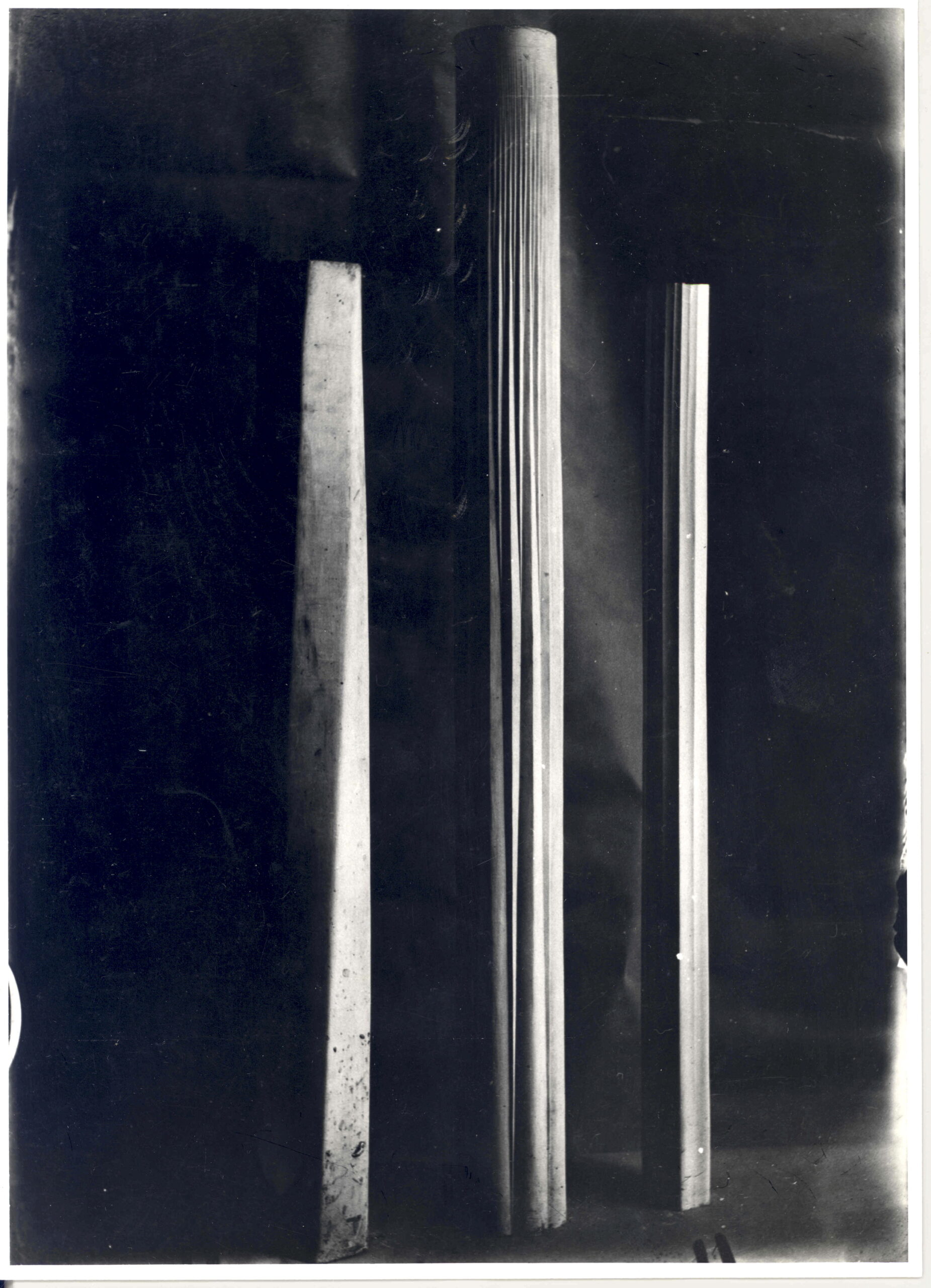

For years, Gaudí used plaster models to study columns that would express this movement and also be strong enough, until he found the definitive solution. The architect invented a column with a polygonal or star-shaped base that gradually turns into a circle as it moves upwards, twisting both left and right from the base. This intersection of two helicoidal twists means that there are more sharp edges the further up the column you go, while the size of the vertexes decreases until, at the top, the polygon is nearly a circle. In each section, in order to double the number of points, it takes half the height and half the rotation each time. The animation below shows how it is made:

Gaudí also achieved a naturalist continuity through geometric procedures, as we see in nature between the trunk of a tree and its branches. This can be seen, for example, in the columns above the choir, which have an intermediate section to prepare for the transition between the lower trunk and the upper branches. The photo and video below explain how these columns are formed:

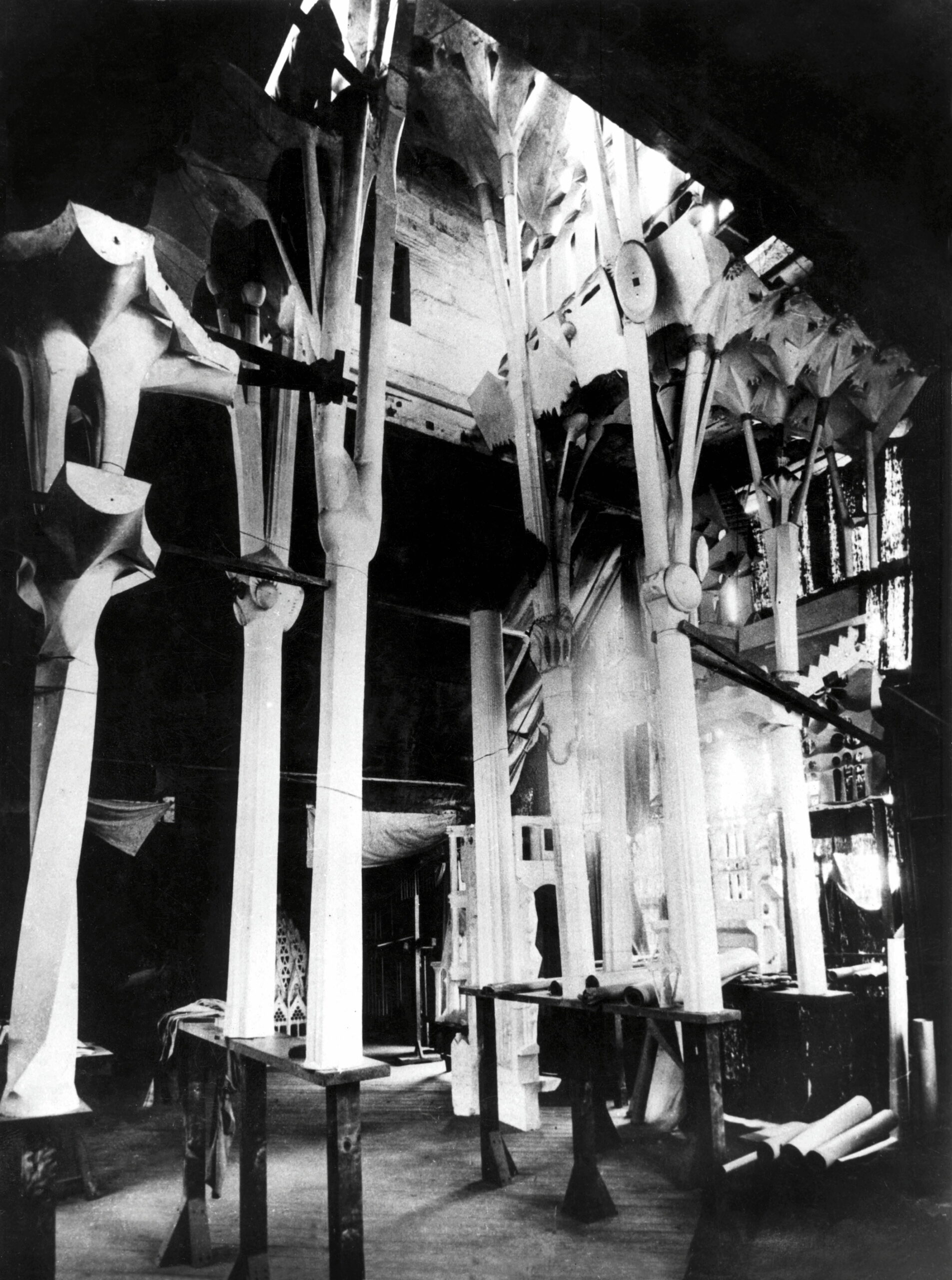

A stone forest

Inside the Temple, Gaudí wanted to recreate a great leafy forest that would help create a feeling of contemplation, as the architect’s assistant Joan Bergós remembers from a conversation with him:

“Intimacy with the spaciousness of the forest, this will be the inside of the Temple of the Sagrada Família.”

Conversaciones de Gaudí con Joan Bergós. Page 42

This is why the structures of the columns and vaults are inspired by the shape of trees, with the shaft imitating the trunk, the capital acting as a knot in the tree and then branching out before it merges with the vaults, which represent the foliage. Plus, Gaudí’s vaults have openings for light to filter through, just like sun rays through the leaves.

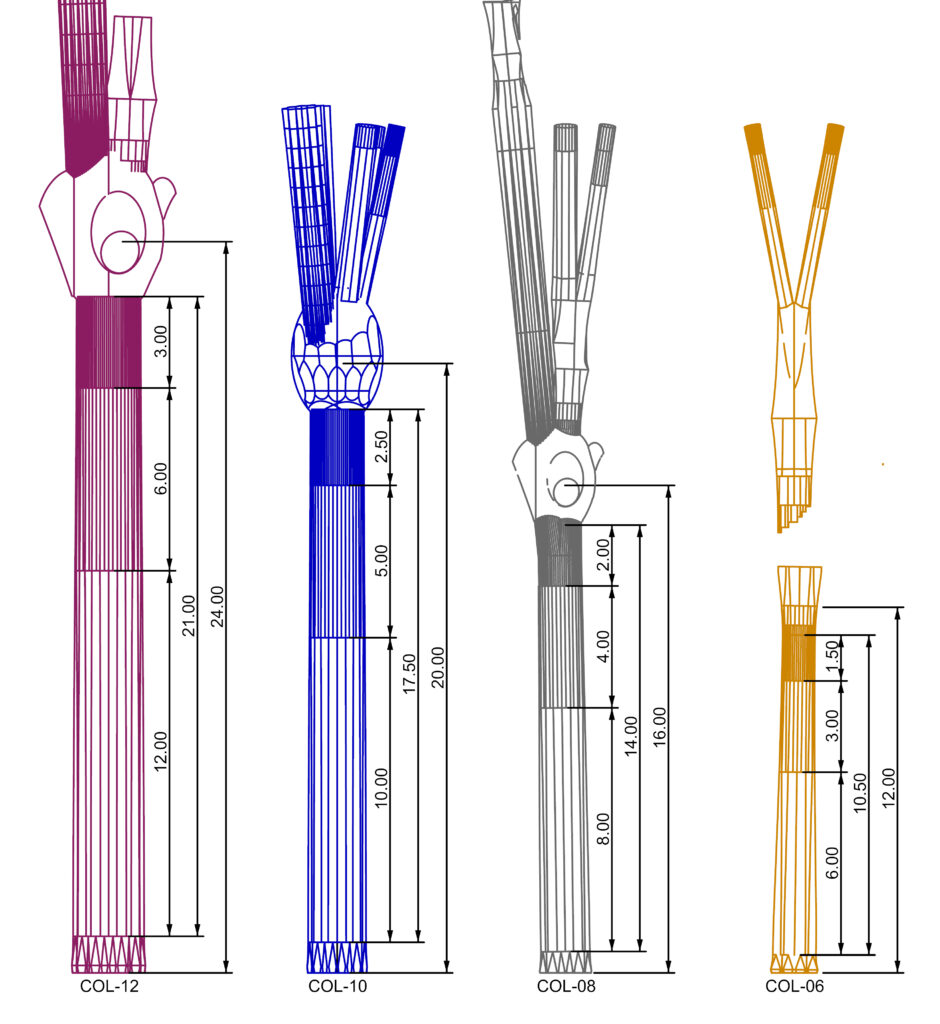

Four types of columns, a structural hierarchy

The main columns inside the Temple follow a hierarchy based on their structural and mechanical importance, meaning what they have to support.

The most important are the four at the corners of the crossing, which have to support the load of the central lantern of Jesus Christ, as well as part of the weight of the four towers of the Evangelists that surround this lantern, plus the proportional part of the vaults and roofs along the way. Second are the eight columns that bear the load of the towers of the Evangelists. They are also located on the crossing, behind the first group. After that, we have the columns in the apse and nave. While those in the apse bear the load of the tower of the Virgin Mary, they are very close together and the same as those in the nave, which support the vaults and attics on the central nave and part of the side naves.Finally, the columns with the lightest load are those that bear the weight of the choir and the side naves.

Gaudí classified these four types of columns based on the elements at his disposal: the star-shaped base, the diameter, the height and the type of stone used.

The star-shaped bases

To make these stars that define each of the groups of columns, the architect always superimposed simpler regular polygons: the equilateral triangle, square and pentagon. So, to make the six-pointed star, he superimposed two equilateral triangles; for the eight-pointed star, two squares; for the ten-sided star, two pentagons; and for the twelve-sided star, three squares.

So, the columns with the most points on the base, twelve, are more important from a hierarchical standpoint, as they are the four at the corners of the crossing. Then come the columns with ten points, then eight and finally six, which bear the smallest load.

In each case, the points of the star are rounded on the inside and outside with tangential parabolic arches. This creates a softly undulating surface at the bottom of the column, where visitors can touch them.

The animation below shows how the base stars are generated for the four types of columns at the Temple:

Diameter and height

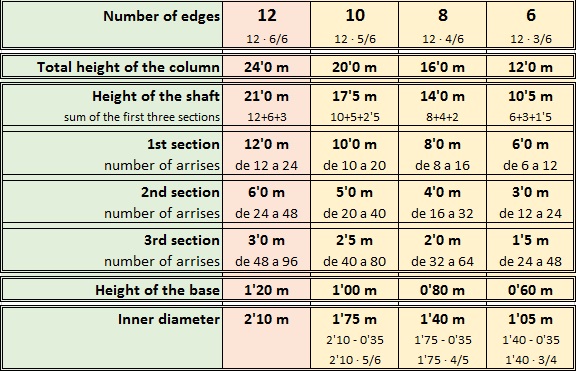

The total height of each column is always, in metres, double the number of points on the star, featuring a base, shaft and capital. The height of the bases is always the same as the number of points in decimetres, while the shaft is always the sum of the first three sections that make it up. Additionally, the inner diameter of each column and the height of the shaft follow the same relation of 1:10, meaning the height of the shaft is always ten times its inner diameter. See the table below:

Also, multiplying the number of sharp edges to infinity, until you get a circle, would complicate the stone-cutting process, so Gaudí simplified it by creating ellipsoid capitals that hide the other sections. So, the circle isn’t visible; it is hidden inside the ellipsoid of the knot or capital.

Colour of the stone

With Antoni Gaudí’s stone tests as a reference, when building started on the columns in the late 1980s, it was decided that the twelve-pointed ones should be red granite porphyry, the strongest stone used in construction; the ten-pointed ones would be black basalt, the eight-pointed columns would be grey granite and the six-pointed ones, yellowish sedimentary sandstone. This choice of materials and colours reinforces the existing hierarchy of the columns and enriches the interior of the Temple.

Gaudí himself realised that the solid stone columns would have to be too big, closing in the space on the ground floor of the Temple. So, as the project evolved, he thought of making the four main columns in iron and probably painted gold, according to a conversation with Cèsar Martinell in 1915 and reproduced in his book Gaudí i la Sagrada Família comentada per ell mateix. In the end, he used reinforced concrete, as his right-hand man Domènec Sugranyes explained in 1923 at a conference he gave on the structure of the Temple at the Association of Architects of Catalonia. So, the stone is the exterior cladding around the inner concrete structure.

Granite porphyry, basalt, granite and sedimentary sandstone columns